The Elemental Cold War

Rare-earths, tariffs, and why resilience can’t be outsourced

Every industrial age begins with a material no one pays attention to. Steel. Silicon. Then one day the world notices who controls it, and everything changes. Rare-earth elements took stage last week when Beijing declared new export rules that effectively gave China veto power over the building blocks of clean energy, defense, and advanced computing.

Washington answered with tariff threats. Markets flinched. Engineers scrolled procurement lists with the quiet panic of people realizing how few options they have.

The Price of Atoms

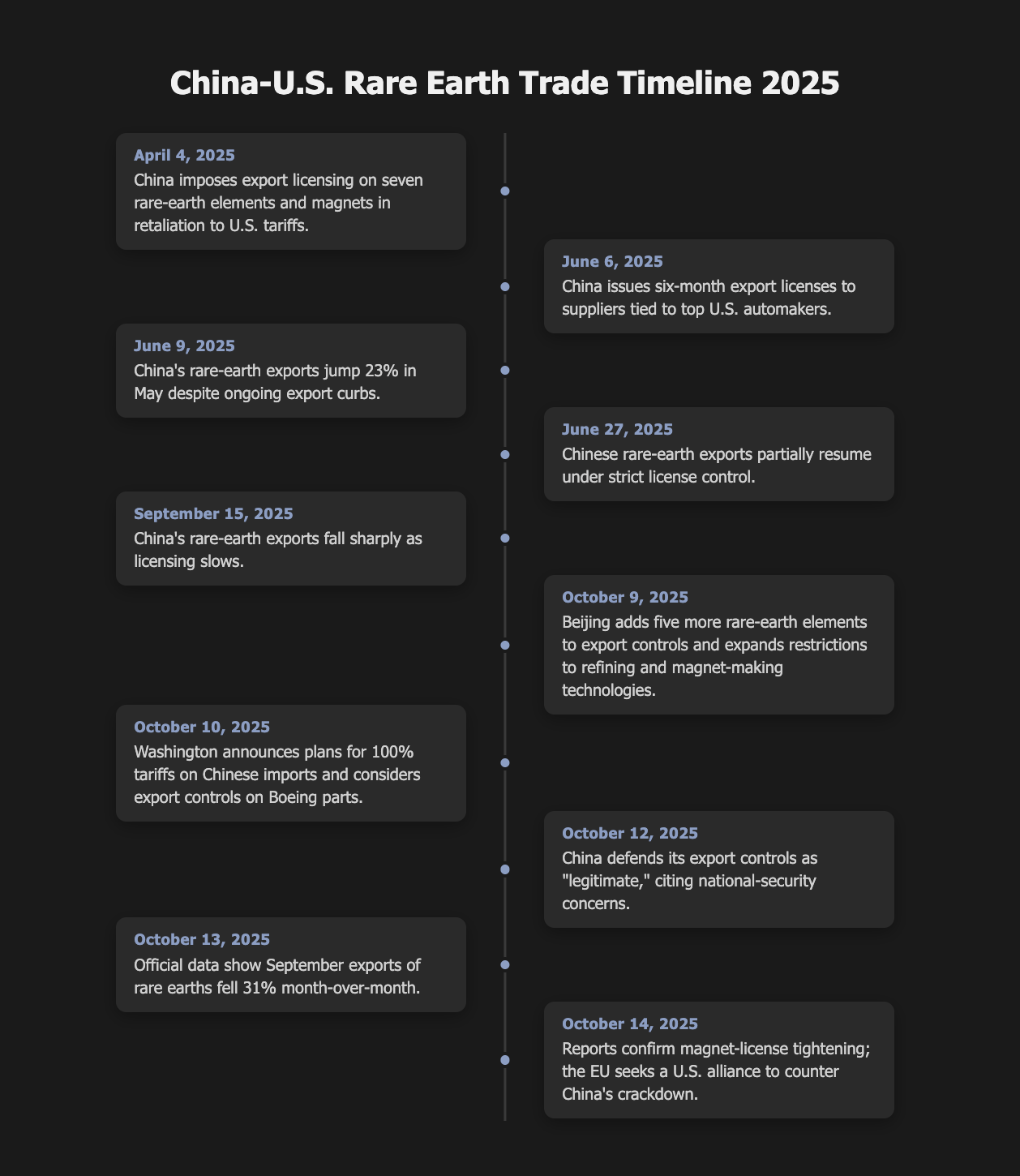

On October 9, 2025, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced that five additional rare-earth elements—holmium, erbium, thulium, europium, and ytterbium—would require export licenses.

The order expanded earlier restrictions on neodymium, dysprosium, terbium, and other magnet metals. It also added dozens of refining methods and magnet-making machines to the controlled-technology list and, most provocatively, applied a foreign-direct-product rule to rare-earth content: any product containing Chinese-origin material could now fall under Beijing’s license regime.

A day later, the White House signaled 100 percent tariffs on Chinese imports and hinted at export controls on Boeing parts. Beijing defended its position as “legitimate,” saying the measures protect national security and prevent sensitive technology from aiding foreign militaries.

How We Got Here

Fifteen years ago, this outcome would have sounded absurd. The West invented most of the extraction and refining chemistry; China industrialized it. Through the 1990s and 2000s, Western manufacturers quietly outsourced the dirtiest steps—acid leaching, solvent extraction, tailings treatment—because they were costly and politically toxic.

China took the deal. It absorbed the environmental costs and mastered the processing science. By the mid-2010s, it mined roughly 70 percent of the world’s rare-earth ore, refined 85–90 percent, and produced more than 90 percent of finished magnets.

Western complacency hardened into dependency. Mountain Pass in California reopened but still shipped concentrate to China for separation. Japan funded recycling projects; Europe passed policy frameworks; little changed. The United States treated rare-earths as a line item, not a strategy.

Beijing saw leverage where others saw waste. In 2010, during a maritime dispute with Japan, it quietly slowed rare-earth exports and demonstrated how quickly prices could spike. The lesson stuck.

By 2020, rare-earths were an unspoken instrument of statecraft—an insurance policy against semiconductor sanctions or military encirclement. When Washington expanded chip-export rules in 2022, the outline of a new trade architecture emerged: the United States controlling logic and lithography, China controlling the periodic table.

The 2025 Break Point

April 2025 marked the first full deployment of that leverage. In retaliation for new U.S. tariffs, Beijing imposed export licensing on seven rare-earth elements and high-performance magnets. Within weeks, shipments slowed. By September, China’s rare-earth exports had fallen 31 percent, and by October the expansion finalized the shift from symbolic to structural leverage. Licenses now apply to a wider set of materials, technologies, and end-uses. A Chinese executive told Reuters that since September, export approvals for magnets have become “significantly harder to obtain.” China was successfully slowing the turnstile.

Any transition away from Chinese processing will likely take a decade of concerted industrial policy. Scaling any breakthroughs in new materials requires years and billions in subsidies.

The Power of the Middle Layer

Control over raw ore matters less than control over processing. Mines can be built; chemistry takes decades to master. The midstream—the sequence of separation, purification, and alloying steps—is where China’s dominance sits deepest.

Every Western plan to “diversify supply” eventually confronts the same bottleneck: no one wants a solvent-extraction facility in their backyard. The waste is toxic and the tailings ponds are permanent. China centralized these costs inside Inner Mongolia and Jiangxi long ago. It built an ecosystem of metallurgists, furnace makers, and magnet fabricators that no competitor has matched.

If you rely on Chinese refineries for intermediate materials, you now rely on Chinese bureaucrats for permission to ship them. Ambiguity becomes a weapon—neither ban nor blessing, just endless paperwork.

Why Substitution Isn’t Simple

Executives love to say “we’ll find alternatives.” They rarely mean it. The physics resist optimism.

Neodymium-iron-boron magnets owe their strength to specific electron-shell configurations that create extraordinary magnetic anisotropy. Replace dysprosium with a non-rare-earth metal and coercivity collapses; motors overheat. Ferrites are abundant but weak. Alnico magnets handle heat but lose strength. A one-percent reduction in magnetic energy product can translate into hundreds of kilograms of extra weight in a vehicle drivetrain.

Laboratories are exploring novel composites, spintronic structures, and rare-earth recycling, but scaling those breakthroughs requires years and subsidies measured in billions. So the rhetoric of substitution masks a deeper reality: any transition away from Chinese processing will likely take a decade of concerted industrial policy.

The Shock Map

The immediate economic exposure spans three pillars.

Energy and transportation. Electric vehicles, wind turbines, and grid generators all rely on neodymium and dysprosium magnets. A shortage raises system costs and delays renewable-energy deployment.

Defense. Guidance systems, radar arrays, sonar transducers, and aerospace actuators all use heavy-rare-earth alloys. CSIS notes that China’s new rules explicitly flag “military and dual-use technologies” as high-risk categories requiring case-by-case review. (CSIS, Oct 2025).

Advanced manufacturing. Robotics, drones, and high-precision tools depend on rare-earth bearings and sensors. Semiconductor fabrication uses specialized polishing compounds derived from cerium and lanthanum, though Taiwan’s industry claims minimal exposure to the newly restricted subset.

The strategic calculus rests on patience. China’s implicit threat: use the rules selectively, pulling the lever only when it wants to extract concessions. But every time it tightens, it accelerates investment elsewhere. Already, Australia, Canada, Japan, the EU, and the U.S. are stepping up rare-earth processing and magnet manufacturing projects. European automakers have sounded alarms. Italy’s metalworking lobby warned that prolonged disruption could derail EV production goals.

For now, few factories have shut down, but procurement chiefs describe a kind of background stress—the need to check every supplier’s supplier, to model who might lose access next.

The Valley’s rhetoric

People are posting threads like this because MOFCOM’s announcement reframed something that had lived in policy circles into a direct economic threat. Twitter (X) became the outlet where technologists, VCs, and operators translated bureaucratic language into existential urgency. The tone—“China just weaponized the supply chain”—isn’t exaggeration so much as shorthand for a structural shift: China now claims jurisdiction over any device containing trace Chinese material. It’s the same logic the U.S. used for chips under the Foreign Direct Product Rule, flipped. For builders and investors, that means hardware supply chains are no longer neutral plumbing—they’re political terrain.

Among venture circles, this sparked a wave of posts about reindustrialization and deep tech realignment. (For more, check out my recent piece on that here.) Investors who once chased software margins now talk about domestic manufacturing, mining startups, magnet recycling, and materials R&D as the new frontier. Hardware founders are seeing inbound interest again, and funds that branded themselves “AI-first” are suddenly scouting battery plants, wafer fabs, and robotics foundries. The consensus shift is fast: the next generation of strategic startups won’t be writing apps; they’ll be writing process recipes, firmware, and metallurgy code. The same people who used to quote Marc Andreessen now quote the CHIPS Act. In that sense, tweets like this don’t exaggerate. They compress a real inflection point where geopolitics, venture capital, and industrial strategy have collapsed into the same conversation.

Strategic gambles and structural limits

China’s power here is formidable. But power concentrated is fragile. China cannot indefinitely freeze output without pushing rivals to invest deeply in alternate capacity. As put by Reuters: “China can only fire the big gun…. once.”

If Western states pour capital into domestic separation, magnet factories, recycling, and supply hubs, China’s choke becomes contested. Its premium as monopoly provider erodes. Field economics will punish overreach.

And for the first time in decades, that punishment might favor the West. Investment in rare-earth processing has tripled across the U.S., EU, and Australia since 2023. Private firms are building capacity faster than governments expected. If even half of those projects reach scale, China’s monopoly starts to crack. Already the EU is leaning in. It seeks cooperation with the U.S. to coordinate countermeasures and diversify sources.

In China’s calculus, timing is key. Tighten before the summit. Force concessions around U.S. chip export rules. Push the narrative: “We have rights too, after decades of U.S. export controls on Chinese tech.” But reputational costs mount: if China is framed as coercive, allies will shift, capitals will invest elsewhere, supply chains will bifurcate.

The threat of retreat is real: foreign capital and mining projects may abandon China’s orbit. Once the chemistry of trust breaks, rebuilding is slow. But disruption breeds innovation. The same geopolitical friction that fractured semiconductors in 2022 now funds breakthroughs in magnet recycling, low-waste extraction, and AI-optimized metallurgy.

What I’m watching (and what you should too)

If Trump meets Xi soon, rare-earths will be on the table. Everything will be bargaining chips. I’m also watching U.S. congressional policy texts… expect a rare-earth industrial act.

Here are pivot points:

License approval times and denial rates. If Chinese authorities begin selective denials to U.S. or allied firms, that’s escalation.

Capital inflows into domestic magnet and refinement projects in U.S., EU, Australia, Japan.

Diplomatic alignments. If G7, EU, Japan join a supply-chain alliance, China’s grip weakens.

New magnet technologies, recycling breakthroughs. If one alternative scale works, the coercion weakens.

Chinese rhetoric. If they escalate to outright bans, not just licensing, we hit a new regime.

Keeping existing hardware viable matters more than ever in this environment. The fewer new components industries need, the less leverage Beijing has over rare-earth supply chains. Extending the lifespan of chips, motors, and devices through better maintenance and refurbishment isn’t just efficient—it’s strategic resilience.

What now?

Software may dominate headlines, but material control—rare-earths, semiconductors, battery metals—defines sovereignty.

China has pushed atoms into the strategic domain. That move forces the rest of us to decide: are we powered by others’ inputs, or will we regain control of our supply base?

When I look ahead, I see two outcomes. One: a bifurcated world where Western supply chains decouple, allies band, and new mining/refining ecosystems arise. Two: a shadow world where we remain partially dependent on someone else’s jurisdiction over materials, afraid of license denials.

I choose the first. But that requires conviction, capital, patience. We need to rebuild not just plants, but industrial will. The worst failure would be to talk about sovereignty and still outsource the atoms. In this moment, a mineral policy becomes the front line of great power competition.

China’s move didn’t invent a new war. It revealed a war already underway at the atomic level. The next decade will tell whether democracies can rebuild their foundations. If they do, this episode fades. If not, it becomes a case study in lost sovereignty.