Truth, information, and control architecture

What happens when the flow of information becomes unpredictable

This week revealed something about power that few want to acknowledge. One inquiry looks upward, at the algorithms that shape what the public sees. The other looks inward, at how institutions manage what we’re allowed to know.

Together, they mark a shift from managing truth to managing its circulation.

On Monday, the U.S. House Oversight Committee summoned Discord, Reddit, Steam, and Twitch to explore how their platforms feed extremism. Days earlier, the Pentagon press corps walked out after officials imposed new rules restricting coverage, access, and questions (rules many saw as an attempt to manage what the public can know).

We are entering a world where our reality depends on infrastructure that no one elected, and almost no one understands.

For most of the last decade, “information control” meant censorship, disinformation, and content moderation. This definition is now insufficient. The mechanisms of influence have moved beneath the surface, into the logic of systems:

who designs them,

who interprets them, and

who can still verify what they produce.

Where This Is Going

What we call “information control” today still sounds polite. Hearings, policies, moderation rules. The real shift is happening under those layers. Control is moving from people to automation systems. We are entering a world where the texture of reality depends on infrastructure that no one elected and almost no one understands.

Once every platform and newsroom optimizes for volume, the system starts eating its own output. Models now scrape AI-written pages to train the next generation of models, feeding on recycled material that contains less information each cycle. Many have argued this will cause a collapse in the models, a point still up for debate in AI research today, where systems trained on their own output lose coherence and accuracy over time. Newsrooms face a similar decay: stories re-edited, repackaged, and reposted until the original reporting disappears. Platforms then push whatever keeps people engaged, regardless of quality. Layer by layer, the system generates a self-referential fog. Information drawn from information, accuracy replaced by pattern.

The problem is not only the bias of the algorithms or the politics of the press. The problem is the feedback loop between both. Governments pressure platforms to remove content. Platforms quietly comply, retrain their models, and filter the next wave of visibility. The public sees less of the negotiation, and the silence begins to look like consensus.

Meanwhile, synthetic content fills the gaps. AI models are now generating so much low-quality material that information itself is turning into waste. The line between data and debris has disappeared. Search results, feeds, and even mainstream articles recycle the same derivative sludge, written for engagement rather than understanding. This isn’t misinformation in the classic sense. It’s decay.

That decay is the cost of scale.

I’m less concerned about people believing lies… we have for centuries, and we’ll continue to do so. I believe the real danger is that people will stop looking for truth altogether. When every channel feels unreliable, control shifts toward whoever can still produce coherence, even if that coherence is manufactured. That’s where power accumulates. Not in owning the facts, but in deciding what still counts as information.

We are not talking about this because we are drowning in the very thing we are trying to understand. The hearings, the walkouts, the platform updates—all of them respond to the surface symptoms of a deeper problem. We built systems that manage attention better than they manage knowledge. Now those systems are starting to manage belief itself.

How Free Speech Became a Moving Target

The phrase “free speech” once had a fixed meaning: protection from government censorship. In the early twentieth century, that principle was tested in courtrooms, not comment sections. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1919 decision in Schenck v. United States introduced the idea of “clear and present danger,” defining when speech could be restricted during wartime. Half a century later, Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) shifted that boundary to prohibit only direct incitement of violence. These rulings anchored speech to law, not to platforms. They drew a clear line between private opinion and state suppression.

The internet blurred that line. When platforms became primary spaces for public discourse, they also inherited a responsibility that was never designed for private companies: to decide what speech stays visible. During the 2010s, “free speech” began to mean something else: access to attention. A tweet or a post could reach millions in seconds, but only if the algorithm allowed it. Visibility became the new form of permission.

The shift accelerated during the 2016 U.S. election, when disinformation campaigns exploited those same systems of visibility. Suddenly, the debate was not whether people could speak, but whether platforms should amplify them. Companies built moderation frameworks, automated detection systems, and advisory boards. The First Amendment no longer described the limits of speech in practice; platform policy did.

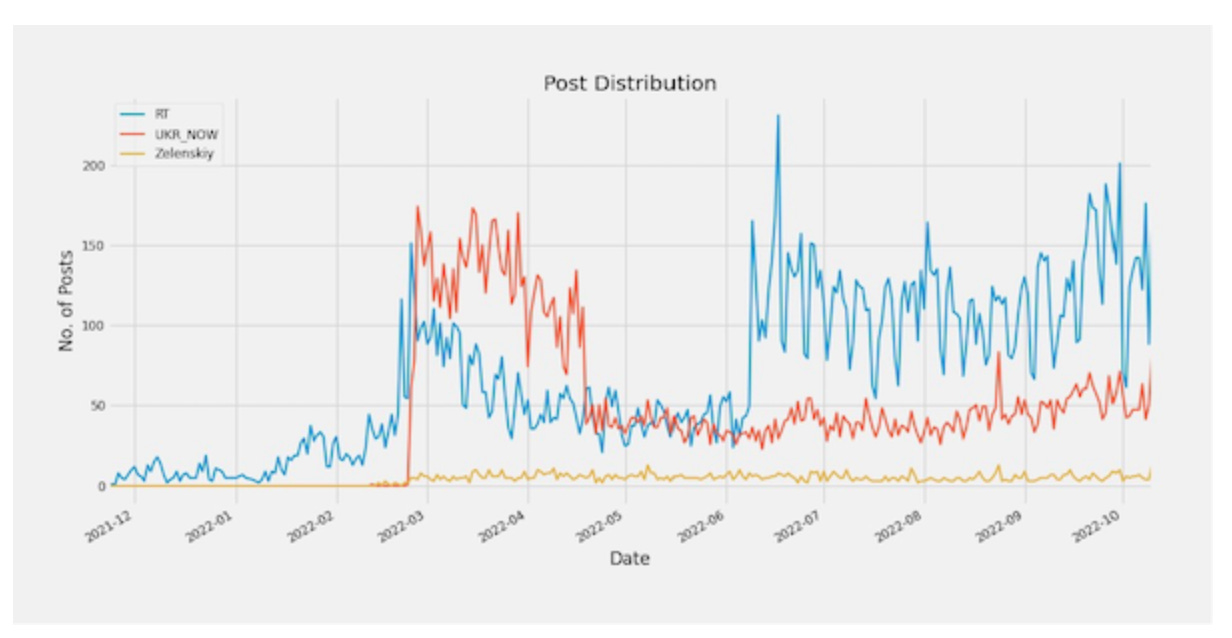

Then came the backlash. The pandemic, the Russia–Ukraine war, and the rise of generative AI each reignited claims of bias and suppression. Governments asked for faster removal of harmful content. Platforms complied selectively, facing accusations of overreach from one side and negligence from the other. “Free speech” fractured into multiple definitions depending on who controlled the distribution system.

Today, the concept depends entirely on infrastructure. Algorithms decide what surfaces. Moderation teams decide what remains. Recommendation loops determine what fades. The old metric—whether a person could speak—has become irrelevant. The operative question is whether anyone can hear them.

This evolution matters because it changes how societies define legitimacy. When speech depends on system design, the architects of those systems become gatekeepers of reality. Lawmakers can subpoena them, users can protest them, and engineers can tweak them, but none of these actions restore a single, shared standard. Free speech has become conditional on architecture. And architecture, unlike law, is invisible to most of the people it governs.

The New Geography of Control

The conversation about control used to focus on what people said. Now it focuses on how information moves. The object of power has shifted from content to infrastructure.

Control today lives inside architecture: the settings, defaults, and feedback loops that decide what circulates and what disappears. Radicalization spreads through those same mechanics. Systems built to keep users engaged also decide which ideas gain traction and which fade out.

Congress’s decision to question Discord, Reddit, Steam, and Twitch shows a late recognition of that reality. Lawmakers want to understand how discovery works, how groups form, and how visibility is distributed. The hearings are not about free speech in the constitutional sense. They are about control over flow. Who shapes attention, who measures risk, and who keeps the logs.

Traditional media faces the same problem in a different form. The Pentagon’s new reporting rules changed the pipeline of defense information. Reporters who walked out were rejecting more than paperwork. They were rejecting a structure that filters who can ask questions and how answers reach the public.

Across government, media, and platforms, the method is the same. When pressure builds, visibility tightens. Each system protects itself by deciding what the public can see. Control has become less about silencing voices and more about managing routes. Each of these systems—government, media, and platforms—has learned the same habit. When the flow of information becomes unpredictable, the instinct is to regulate circulation rather than restore trust. The more those controls expand, the more fractured the information landscape becomes.

That fracture defines the next stage.

Collapse of Shared Sources

There was a time when truth had addresses: newspapers, agencies, academic journals. Each had bias, but also boundaries. Those boundaries created accountability. Today that map is gone. The internet multiplied sources faster than trust could scale. Social networks made information abundant but stripped away context.

And now, GenAI has essentially made content production infinite. The volume of material has grown beyond human verification, eroding the signal-to-noise ratio that once gave information value. Attempts to stop misinformation remain weak. Most watermarking and content-credential systems fail once material is reposted or edited, stripping away metadata meant to signal authenticity. Even when capture devices embed provenance data, most platforms discard it before publication. The result is an inversion of credibility: the easier something is to see, the harder it is to prove.

Platforms no longer host conversation. They govern it, shaping what looks credible through engagement metrics, moderation filters, and opaque distribution systems. The new architecture of truth is statistical, not editorial. What appears true is whatever the system can measure.

The more control fragments, the more governments look for ways to contain it. I keep coming back to one question I’ve heard in a few recent conversations: are we following the same path as Turkey?

A Mirror in Türkiye

Turkey’s system of control did not appear all at once. It grew through laws, national security language, and quiet pressure on platforms to align with government priorities. Each step sounded reasonable. Together, they built an architecture of control.

Earlier this year, Turkish officials blocked more than 27,000 social media accounts for alleged disinformation and threats to stability. In September, access to X, YouTube, and WhatsApp was throttled during political unrest, forcing citizens to use VPNs to communicate. On Sept 10, “Proton VPN recorded a spike of over 500% on an hourly basis on Sunday night.” Those actions were presented as temporary, but the controls stayed in place.

The parallel is uncomfortable. The United States still debates control through hearings and press policy, but the logic is similar. The hearings, subpoenas, and press restrictions aren’t the same thing, but they do rhyme. Once information flow becomes a matter of “national interest” or “public safety,” it’s easy for access limits to feel justified. Over time, control stops looking like censorship and starts looking like maintenance. The line between protecting the public and managing the public begins to blur.

The Press and the Problem of Nerve

The Pentagon story (or.. lack of future stories?) exposes how traditional news and social platforms now sit on opposite ends of the same problem. Both control what reaches the public, but in different ways.

Social media systems flood information. Every perspective can surface, but algorithms decide which ones last long enough to be seen. Attention replaces verification. Outrage keeps the machine running. The result is a public square that never stops talking but rarely listens.

News outlets work in the reverse. Access is scarce, movement is restricted, and stories depend on permission. Access is limited, movement is constrained, and stories depend on permission. When the Pentagon tightened its rules for reporters, many had to decide whether to stay and work under those limits or to walk out and lose the story altogether. The dilemma mirrors what platforms face when deciding how to moderate content. One filters to manage risk, the other to preserve access. Both end up shaping perception, instead of widening knowledge and understanding. Both systems claim to inform the public. Both systems now define truth through what they can afford to show.

This is the new problem of nerve: whether to preserve reach or preserve credibility. Platforms risk chaos if they stop moderating. Newsrooms risk irrelevance if they lose access. Each structure bends under the pressure to stay visible in a system that rewards control more than clarity.

What We Should Ask

The next phase of this debate will hinge less on technology than on reasoning. For every new rule, tool, or regulation that claims to defend truth, the public should ask:

What harm does it reduce, and how is that harm measured?

Through what mechanism does it act?

What data would demonstrate success or failure?

How reversible is the control once the crisis passes?

Who gains and who loses the capacity to verify independently?

These questions matter because control over information systems is rarely neutral. It always redistributes power—sometimes away from governments, sometimes away from the public.

A Systemic Future

Control is converging. Governments, media, and platforms are adopting the same tools: rate limits, algorithmic filters, gated access, provenance metadata. Each believes these will restore trust. None seem to notice that they create interlocking dependencies where verification depends on the very systems being verified.

Truth will not collapse in a single event. It will thin out. It will become conditional on access, visibility, and computational traceability. The Pentagon can limit physical access; platforms can limit digital reach; AI can blur both by fabricating credible artifacts faster than humans can review them.

The future of information integrity depends less on censorship and more on architecture. If transparency, accountability, and verification exist at the level of design, institutions can recover trust. If not, every new safeguard will deepen the same instability it claims to prevent.

This week’s hearings and the Pentagon walkout are not separate stories. They are signals from opposite ends of the same system—one public, one closed—each negotiating the boundaries of truth. The question that follows is not who is right but who still has the capacity to observe. Because when systems of observation fail, control becomes the only remaining form of order.

great work