Vertical Stacks, Horizontal Dreams

How defense tech is exposing the trade-offs in AI and data infrastructure—and what Silicon Valley should learn from Palantir and Anduril.

If you’ve never worked in defense, “command, control, and communications” (C3) can sound abstract. Think of it as the connective infrastructure of the U.S. military: sensing what’s happening, deciding what to do, and passing orders across thousands of units in tough conditions.

Over the last two years, the Pentagon has poured much energy into wiring this infra end-to-end—connecting satellites, jets, and soldiers—under banners like the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) and the Pentagon’s Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2). The aim is deceptively simple: get the right data to the right decision-maker faster than any adversary, even under jamming or cyberattack.

At the same time, Silicon Valley’s favorite tension—vertical vs. horizontal tech—hit defense software. Instead of neutral platforms that sit above everything, companies like Anduril are bundling hardware, software, and networking into tightly integrated stacks. Others, like Palantir, lean into the data-platform model, promising to be the connective tissue across missions. Both approaches are gaining traction. Yet neither fully solves the Pentagon’s core problem: how to make data and AI infrastructure resilient, interoperable, and adaptable at scale.

Defense is a case study, but the tension is universal: vertical smoothness vs. horizontal interoperability. For the DoD, it will decide whether command and control survives the next war. For Silicon Valley, it signals where the next wave of enterprise value will be created.

What shifted in 2024–2025

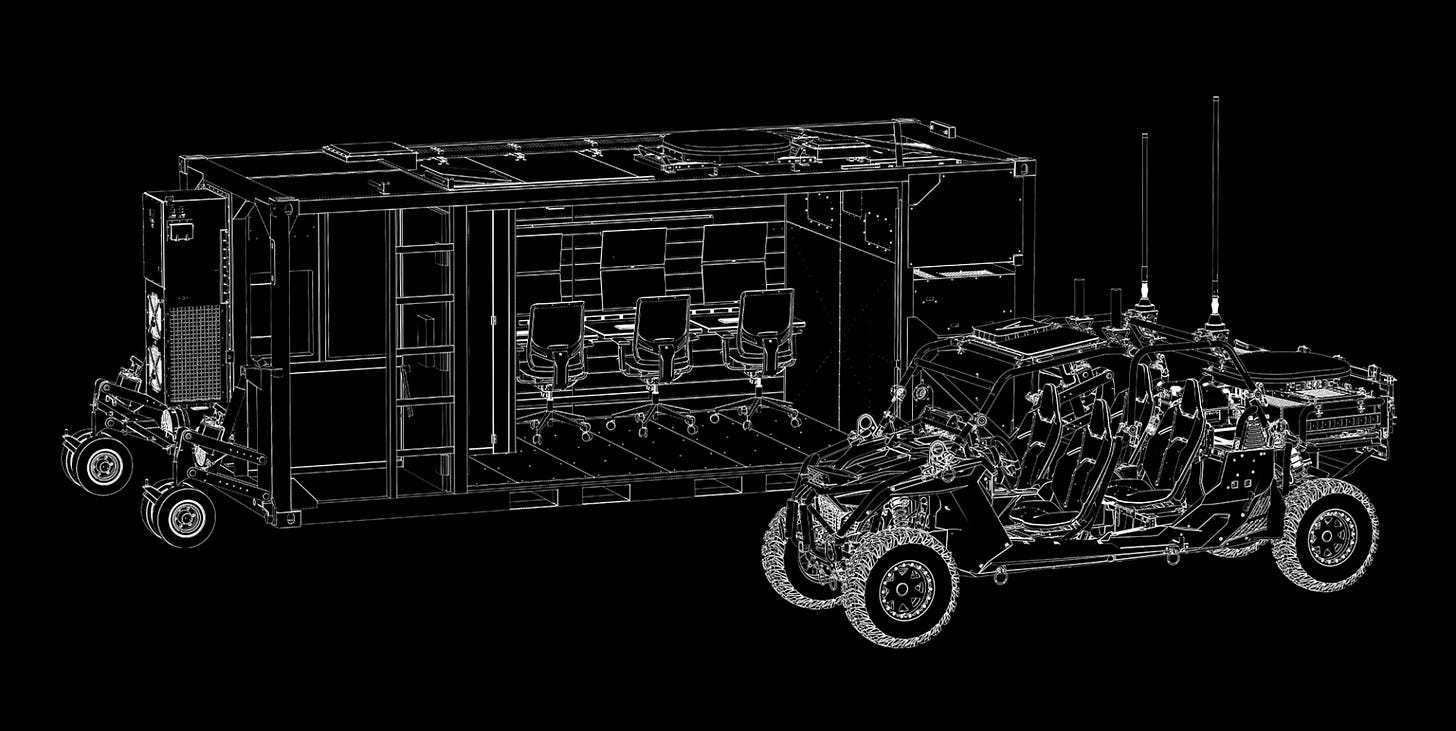

The Air Force finally moved ABMS from slideware to fielding. In 2025, the Air Force began using new TOC-L kits: mobile command centers that fit into just one cargo plane, rather than six. That kind of compression isn’t cosmetic. It changes how fast battle managers can move and reestablish command nodes in the Pacific, where bases are exposed and agility is survival.

CJADC2, the broader attempt to connect every service, also showed progress. But a GAO review warned that the Pentagon still lacks a common framework and that branches are building in isolation. Everyone wants the same outcome, but the roadmaps don’t line up.

To anchor priorities, the DoD’s CTO office elevated Integrated Network Systems-of-Systems (INSS) as a critical technology area, calling for networks that allow “any sensor” to cue “any shooter” even in contested electromagnetic environments. It’s a clear signal: the Pentagon now views data infrastructure as the foundation of combat power, on par with missiles or aircraft.

The resonance with Silicon Valley is direct. Palantir looks like Snowflake or Databricks: horizontal platforms where data is modeled and apps can be built. Anduril looks more like Apple: own the hardware, own the OS, deliver something that works out of the box.

Horizontal vs. vertical tech

1/ Palantir’s platform gravity

Palantir embodies the horizontal thesis: provide a data and application layer that lets programs plug in, share, and build. The Army’s 2025 enterprise agreement—consolidating seventy-five contracts into a single 10-year, $10B deal—reflects that appeal. Palantir also secured the Maven Smart System contract, extending its AI footprint into core targeting workflows.

But Palantir is not as horizontal as it appears. Its Ontology is the operational layer where apps, permissions, and workflows live. Once data is modeled inside it, the center of gravity shifts inward. Apps accelerate, but integration beyond that boundary gets harder. That’s why the Army standardized instead of letting dozens of Ontologies proliferate. Palantir helps within a service, but GAO’s warning still stands: the Pentagon lacks a cross-service framework, and its Foundry platform alone won’t create one.

2/ Anduril’s vertical stack

Anduril chose to own the stack. Its Lattice OS integrates drones, surveillance towers, undersea vehicles, and, after the 2025 acquisition of Klas, ruggedized comms trusted at the tactical edge. The appeal is obvious: units in the field don’t want to troubleshoot integrations, they want gear that works out of the box.

That control, though, brings trade-offs. Anduril positions Lattice Mesh as the connective tissue linking thousands of systems, including third-party hardware, but the center of gravity is always Lattice. The company’s incentive is to expand its ecosystem, not to federate with competitors. For buyers, the risk is lock-in disguised as interoperability: seamless inside the Anduril world, but harder to carry outside it. That’s the challenge as CJADC2 pushes for cross-service and coalition interoperability.

The edge and the cloud

“Edge compute” is the buzzword, but the edge comes in layers. A ruggedized ‘Azure Stack Edge Pro R’ or ‘AWS Snowball Edge’ at a forward base is very different from an AI model running on a drone. Startups like Armada are containerizing modular data centers: forward “clouds” that can be shipped and powered anywhere.

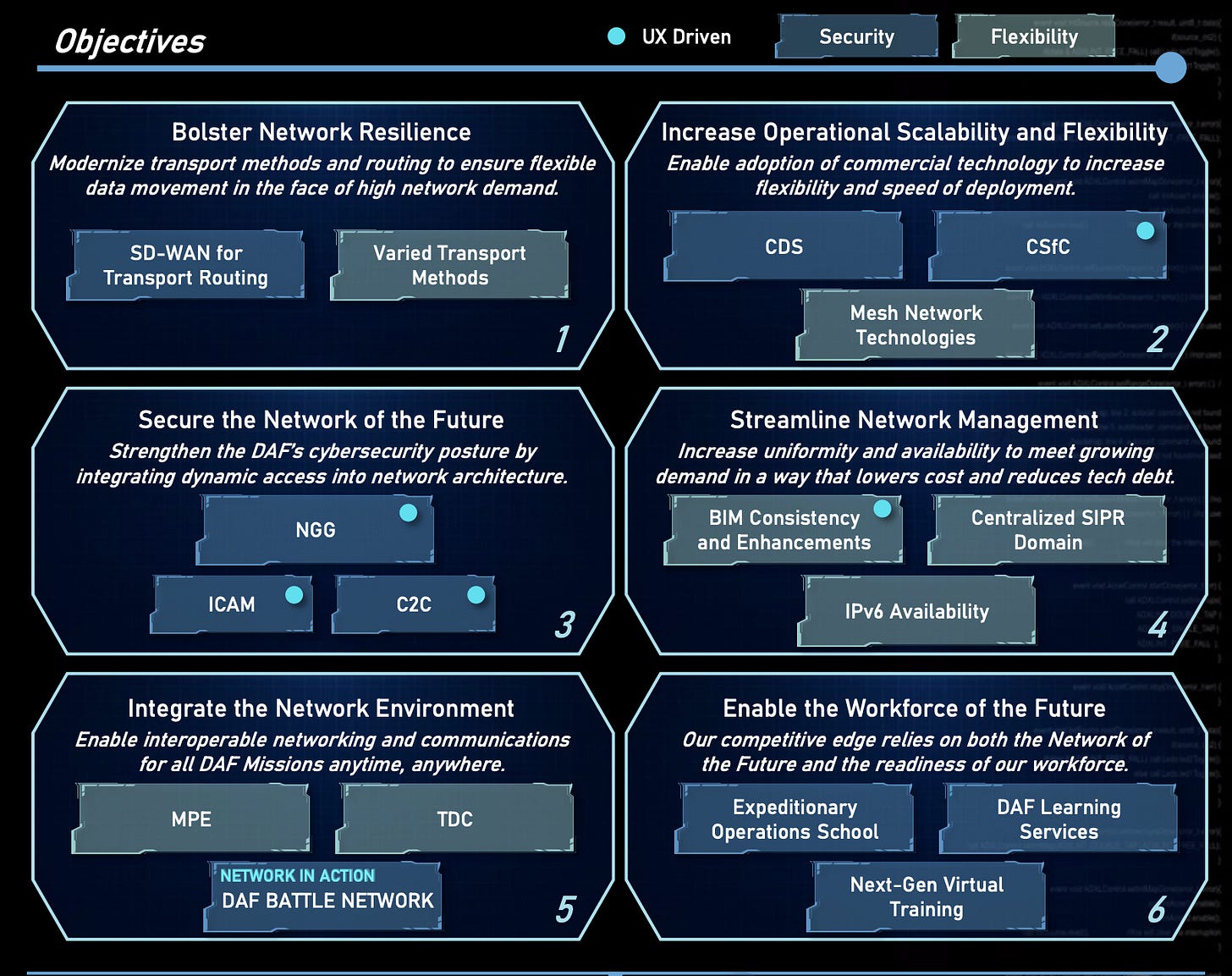

In 2025 the line between forward cloud and true tactical edge blurred. Anduril’s Klas deal is one example, merging Lattice with routers already used in SOCOM kits. The Air Force’s “Network of the Future” vision is another, calling for a secure, encrypted mesh that keeps C3 working even when satellites or undersea cables are cut.

This distinction matters because the Pentagon can buy forward cloud from hyperscalers, but true tactical edge compute still lags. An AWS data center in a container is not the same a drone running its own AI under jamming conditions. That gap is one of the biggest opportunities for new startups.

Why is comms so difficult?

The Pentagon isn’t starting fresh. It still operates over 15,000 separate networks, each with unique rules, crypto, and authorities. Even in 2025, industry leaders complain that silos and classification rules force bespoke solutions to problems that are “95 percent identical,” driving cost and slowing delivery.

That’s why INSS emphasizes interoperability. FutureG, software-defined radios, and open data fabrics aren’t optional, they’re prerequisites for survival. Vertical stacks like Anduril’s still need to plug into common exchange standards if “any sensor, any shooter” is to mean anything.

What the Pentagon still wants (and isn’t getting)

The last two years proved that the Department of Defense can buy platforms and field new kits. What it still hasn’t cracked is the connective tissue. A Government Accountability Office review in April 2025 praised momentum but noted the obvious: there is still no unified framework guiding CJADC2 investments, and each branch is building data-integration capabilities on its own. In practice, that means the Air Force may wire its battle network one way, the Army another, and the Navy a third. The silos get smaller and faster, but they are still silos.

There’s also the problem of pace. Palantir’s $10B enterprise agreement and Anduril’s expanding Lattice ecosystem show the Department is willing to spend big, but acquisition cycles still look like multi-year waterfalls rather than agile software pushes. Maj. Gen. Luke Cropsey, who leads Air Force C3 modernization, has argued that capability needs to ship “today, not in months or years”. Right now, procurement speed and software iteration live in different centuries.

What DoD wants is clear: interoperable data fabrics that can flex across services, resilient AI-enabled comms that survive jamming, and contracting models that don’t freeze technology in place. What it has is progress in pieces, but not yet the whole infrastructure picture.

Lattice Mesh serves as the core networking capability, supporting all of our Lattice solutions, to include Command and Control (C2) and Mission Autonomy (MA). Today, Lattice Mesh is connecting thousands of Anduril and Third-Party systems across the world in support of real-world operations.

Lessons for Silicon Valley

Palantir and Anduril point in opposite directions: one as a horizontal platform with gravitational pull, the other as a tightly integrated vertical stack. Both expose the gaps. Palantir accelerates deployments inside a boundary but struggles to federate across services and allies. Anduril delivers speed and resilience at the edge but risks lock-in and limited breadth. Neither model alone provides the resilient, interoperable AI and data infrastructure that efforts like CJADC2 and INSS demand.

For startups, the signal is clear: the future is hybrid. Vertical stacks will dominate where reliability matters most: at the tactical edge, under jamming, off-grid. Horizontal data fabrics will matter most where interoperability is essential — across services, coalitions, and legacy systems. The Pentagon’s push for Open DAGIR, a government-owned data mesh, underscores that big customers eventually demand open standards to keep vendors honest.

The resonance with Silicon Valley is direct. Palantir looks like Snowflake or Databricks: horizontal platforms where data is modeled and apps can be built. Anduril looks more like Apple: own the hardware, own the OS, deliver something that works out of the box. The same trade-offs play out in commercial AI. OpenAI’s closed API model is the vertical bet. Open-source foundation models are the horizontal one. Will either win outright?

Defense tech is the proving ground. If Palantir can’t make Ontologies interoperate across services, that’s a lesson for every “horizontal” AI company that quietly traps data inside its runtime. If Anduril’s stack falters in coalition operations, it’s a cautionary tale for any startup betting its future on proprietary ecosystems.

The companies that thrive will be those that deliver deployable, opinionated stacks while exposing open, standards-based hooks. They won’t only win Pentagon contracts; they’ll also set the pattern for how AI infrastructure matures across industries. Defense shows the stakes most starkly: if the connective infrastructure fails, wars are lost. In Silicon Valley, the consequence is market share instead of lives, but the architecture choices rhyme.

Why it matters beyond defense

This isn’t only about Pentagon acronyms. It’s about how the largest technology buyer in the world is choosing to modernize its AI and data infrastructure. The Army’s Palantir deal looks like an AWS enterprise license. Anduril’s model looks like Apple’s. Open DAGIR looks like the government’s version of open standards.

Defense is a case study, but the tension is universal: vertical smoothness vs. horizontal interoperability. For the DoD, it will decide whether command and control survives the next war. For Silicon Valley, it signals where the next wave of enterprise value will be created.

The bottom line: Verticalization solves the last tactical mile. Interoperability solves the first strategic mile. The future belongs to those who can meet in the middle: fast at the edge, fluent across the network.