When 20% of the Internet Blinks

The concentration risk nobody wants to fix

We’ve built the entire Internet on four companies, and it’s making me lose my mind.

Maybe, just maybe, critical infrastructure shouldn’t depend on whether Cloudflare, AWS, Azure, or Google had a good morning.

Yesterday morning, Cloudflare went dark. 6:48 AM ET. X stopped loading. ChatGPT threw errors. Spotify went silent. Thousands of sites displayed the same message: “internal server error on Cloudflare’s network.” Even Downdetector (the site where you check if the Internet is broken) was down. Because it runs on Cloudflare. 🤡

Three hours later, fixed. CTO Dane Knecht apologized: “We failed our customers and the broader Internet.” Shares dropped 2%.

We shouldn’t move on and forget. Because this is the third major infrastructure failure in a month. AWS collapsed in October. Azure and Microsoft 365 went dark before that. CrowdStrike in July. Each time, millions of people stare at loading screens while engineers scramble. Each time, we’re reminded that the Internet—this thing we treat as a utility, as essential infrastructure—runs on a handful of private companies that can blink out whenever their internal systems hiccup.

Cloudflare handles 20% of web traffic. One in five sites you visit depends on their network staying up. And yesterday it didn’t. Not because of a cyberattack or some sophisticated breach, but because of unusual traffic patterns that caused internal service degradation. Translation: Cloudflare broke under its own operational weight.

Here’s the thing that makes this infuriating: the distributed architecture we’ve been sold as resilience theater is sitting on top of control systems that are anything but distributed. Cloudflare nodes across Europe went down simultaneously—Bucharest, Zurich, Warsaw, Oslo, Amsterdam, Berlin, Frankfurt, Vienna, Stockholm, Hamburg. All at once. Geographic diversity means absolutely nothing when the failure happens at the orchestration layer.

We’ve been told edge computing would save us…. But when the brain that tells all those distributed nodes what to do goes offline, the whole network is just expensive infrastructure sitting idle. And tbh I don’t think we should call what Cloudflare does as actual “edge” computing in the first place. It’s still centralized.

The Real Architecture of the Edge

Cloudflare operates in 330 cities across more than 120 countries. That’s the pitch: we’re everywhere, so we’re fast. Cloudflare claims 95% of the world’s Internet users are within 50 milliseconds of one of their servers. For most applications, that latency advantage matters. A user in London loading a site hosted in New York gets the data from a Cloudflare server in London. The content is cached at the “edge” (at mini data centers outside cities, known as PoPs). The experience feels instant.

But the edge strategy only works if the control plane stays up. And that’s where things get complicated.

Cloudflare doesn’t own the data centers. It leases space in all its cities, which keeps capital expenditures low and allows rapid global expansion. The company runs its full service stack at every location, meaning every point of presence can handle caching, DNS, security, and compute. That density is the moat. AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud Platform can’t replicate 330+ edge locations overnight.

But density creates dependencies. Cloudflare’s global network is programmable, meaning traffic gets routed to the best available data center in real time. The system uses BGP and Segment Routing MPLS to steer traffic across predetermined paths. Once traffic enters the network, it stays on Cloudflare’s backbone until it exits. No detours. No reliance on the public Internet.

The backbone is the critical asset. Since 2021, Cloudflare has increased backbone capacity by more than 500%. The company completed a global ring in 2023 by adding sub-sea cable capacity to Africa, connecting six continents through terrestrial fiber and undersea cables. The investment pays off in performance. Cloudflare measured that origin requests from Johannesburg to various locations were up to 22% faster when carried over the backbone compared to the public Internet.

The problem is that the backbone needs a brain. Argo Smart Routing makes real-time decisions about which path to use. Orpheus detects degraded routes and reroutes traffic automatically. These systems work beautifully when they work. But yesterday, while the distributed architecture kept running in most places, the control systems that decide where traffic goes and how services recover went offline. The network had no way to route around the problem because the problem was in the routing itself.

The Business Model: Hooks and Expansion

Cloudflare’s market position looks unassailable from the outside. The company holds 39.24% market share in the CDN space, with Amazon CloudFront at 24.22% and Facebook CDN at 13.79%. Cloudflare serves more than 80% of websites that use a CDN. It’s not even close.

But the customer base splits into two worlds. Small and medium-sized businesses make up the bulk of the numbers. Enterprise customers generate the revenue. Akamai, despite having far fewer customers, dominates in revenue terms with 30-40% market share because it serves the Fortune 500. Cloudflare is building toward that market, but it’s not there yet.

The entry model is brilliant. Cloudflare’s Workers platform charges $0.0000001 per operation. Developers start with the free tier, scale up as usage grows, and eventually find themselves paying $10,000 a month for Workers, Databases, and Security. The freemium funnel works because once you’re in, migration costs are high. The code runs at the edge. The routing is optimized. The security is baked in. Switching means rewriting the stack.

The free tier also generates data. Cloudflare sees real-time traffic patterns across millions of websites. That visibility feeds into product development for security, DDoS protection, and AI inference. The more users on the platform, the better Cloudflare gets at detecting threats and optimizing performance. It’s a network effect, but one built on telemetry rather than user behavior.

Revenue growth has been consistent. Cloudflare reported $656.4 million in 2021, a 52% year-over-year increase. In Q2 2022, revenue hit $234.5 million, up 54% year-over-year. The company is scaling, but profitability remains elusive. Free cash flow can’t compete with AWS, Azure, or Google when it comes to winning enterprise deals. The hyperscalers bundle CDN with storage, compute, and machine learning. Cloudflare sells speed and security. That’s a narrower pitch.

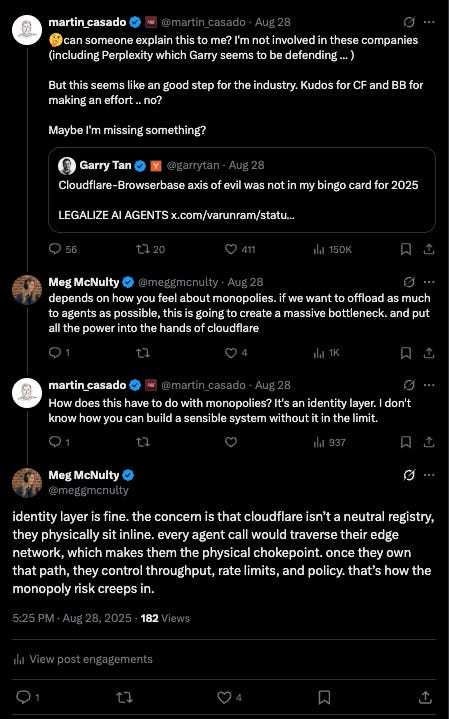

The AI Agent Bet (That Might Not Pay Off)

Cloudflare sees the agentic web coming and wants to own the payment rails. Big if true.

The company launched Pay per Crawl in July 2025, a marketplace where website owners set prices for AI crawlers. The system works through HTTP 402 responses. When a crawler hits a paywalled page, Cloudflare returns a price. The crawler decides whether to pay. If it does, Cloudflare charges the AI company and distributes the earnings to the publisher. Simple. Elegant. Completely unproven.

The economics are catastrophic for publishers right now. OpenAI’s crawler scrapes 1,700 times for every referral it sends back. Anthropic scrapes 73,000 times per referral. Google’s ratio is 14 to 1. The old model—let Google scrape in exchange for search traffic—made sense when Google sent people to your site. The new model, where ChatGPT or Claude answers the question directly without attribution, breaks that deal entirely.

Cloudflare is betting that AI agents will need a programmatic way to negotiate access. The pitch sounds compelling: give your agent a budget, let it crawl premium content, and pay micropayments as it goes. But the business model is undefined, and Cloudflare admits it’s “way too early” to forecast revenue. That’s corporate-speak for “we have no idea if this will work.”

The risk runs deeper than failed monetization. If publishers can’t make money in an AI-first world, they stop publishing. If the volume of quality content on the web declines, Cloudflare’s entire ecosystem shrinks. The company is trying to solve this with Pay per Crawl, but it requires coordination between publishers, AI companies, and end users. That’s a massive coordination problem with zero precedent.

Meanwhile, Cloudflare is building infrastructure for AI agents like it’s already a solved market. The company released agents-sdk, a JavaScript framework for building agents that can call models, persist state, schedule tasks, and browse the web. The architecture runs on Workers, which bill by CPU time instead of wall-clock time. When code waits on an LLM response, you’re not paying for the wait. That makes Workers cheaper for AI workloads than traditional serverless platforms.

Workers AI provides serverless inference on GPUs distributed across the edge. Developers can run models close to users without managing infrastructure. The pricing model is pay-per-call. No idle GPU costs. No reserved capacity. It’s efficient for the workloads that need it.

But here’s the question nobody’s answering: does the agentic web actually happen? Cloudflare is building the plumbing before anyone’s proven there’s demand for the water. And if the agents don’t show up, all this infrastructure is just more sunk capital chasing a market that might not materialize.

The Competition: Who Actually Owns What

Akamai still owns the enterprise market, and that’s not changing. The company operates one of the world’s largest CDN networks with over 300,000 servers. Fortune 500 companies trust Akamai because it’s been around longer, because the scale is proven, and because the security portfolio is enterprise-grade. Cloudflare is growing into that space. Akamai isn’t ceding ground.

Amazon CloudFront is the real threat. If you’re already on AWS—and who isn’t—adding CloudFront is frictionless. The integration is seamless. The pricing is competitive. AWS views Cloudflare as its top competitor in the serverless space, according to a former AWS Lambda lead. That’s the battlefield.

Fastly carved out a niche with ultra-fast content delivery and developer-friendly tools. Smaller—$543.7 million revenue in 2024, 7% year-over-year growth—but focused. Fastly wins on real-time tuning and low latency for live streaming or API acceleration. Fewer points of presence than Cloudflare, but strategic placement for specific use cases.

Cloudflare’s competitive advantage is the sunk capital. Most of the infrastructure is already deployed. That gives the company pricing leverage over competitors who need to build equivalent global presence. But the hyperscalers have deeper pockets, and Cloudflare can’t outspend AWS, Azure, or Google in a pricing war.

The weakness is obvious: cash flow. Cloudflare doesn’t have the free cash flow to compete head-to-head with the hyperscalers for large enterprise customers. The company has to win on performance and simplicity. That’s a tougher sell when the buyer is already locked into AWS or Azure for compute, storage, databases, and machine learning. Why add another vendor when CloudFront is right there?

The Concentration Problem Everyone Knows About But Won’t Fix

Yesterday’s outage wasn’t an anomaly. It’s what happens when you let Internet infrastructure consolidate into four companies and call it innovation.

Cloudflare, AWS, Azure, and Google handle the majority of Internet traffic. When one fails, huge chunks of the web go offline. The failures are accelerating. AWS went down last month. Azure failed before that. CrowdStrike caused a global outage in July with a bad software update that grounded flights and shut down hospitals. The pattern is obvious: centralized control, distributed consequences.

The paradox is brutal. Edge computing was supposed to fix this. Distribute the workload. Run code close to users. Eliminate single points of failure. But the orchestration layer—the control plane that decides where traffic goes and how systems recover—is still centralized. It’s a single point of failure dressed up in geographic distribution. When it breaks, the whole network goes dark, and we’re left staring at error messages while someone at Cloudflare HQ pushes a fix.

Here’s what nobody wants to say out loud: the companies best positioned to provide reliability at scale are the exact same companies whose failure creates the largest impact. That’s not a bug in the system. That’s the system working as designed. We optimized for efficiency and convenience, and we got brittleness and concentration.

The infrastructure layer is becoming a geopolitical asset. Governments are treating compute and connectivity as strategic resources. Europe launched AI gigafactories to secure compute sovereignty. The U.S. is tightening export controls on chips. China is building domestic infrastructure to reduce dependence on Western cloud providers. Cloudflare operates globally, which makes it both a target for regulation and a partner for data localization.

The November 18 outage resolved in hours. Cloudflare’s engineers did their job. But the structural problem isn’t going away, and it’s getting worse. The Internet runs on a handful of companies. Edge computing distributes compute geographically, but it doesn’t distribute control. And control is where the failures happen.

I’m watching every new cloud deal, every new CDN contract, every decision to “just use Cloudflare” add another dependency to a system that’s already too concentrated to be stable. We built the Internet to route around damage. Then we handed the routing tables to four companies and hoped for the best.

How’s that working out?